The Story of the First ACO Wildlife Tunnel*

In 1987, a project was initiated by the Fauna and Flora Preservation Society, Inc. in Boston to install a pair of tunnels to facilitate movement of spotted salamanders Ambystoma maculatum across Henry Street in Amherst, Massachusetts. Drift fences and tunnels had been used to aid toads migrating across roads in Europe, however, a project of this kind had never been attempted for mole salamanders. The Henry Street project offered an opportunity to evaluate whether techniques used in Europe would work for salamanders in New England.

Spotted salamanders breed in temporary ponds early in the spring. Several aspects of their biology present unique challenges for drift fence design. Spotted salamanders are fossorial; therefore the bottom 6-10 cm of the drift fence must be buried in the ground. In Massachusetts, breeding migrations occur in late March, while the ground is still frozen. As a result, drift fences must be installed in fall or early winter, before the ground freezes. Spotted salamanders can climb, and steps needed to be taken to prevent them from climbing over fences. Drift fences have been used to census spotted salamanders, but pitfall traps are usually placed no more than 3-5 m apart along a fence. At the time, it was not known whether salamanders would move longer distances along a drift fence.

ACO, Inc. supplied two tunnels that were installed in time for the 1988 spring migration. For reference, the focus was on three concerns: flooding, effectiveness of drift fences, and effectiveness of tunnels.

Flooding

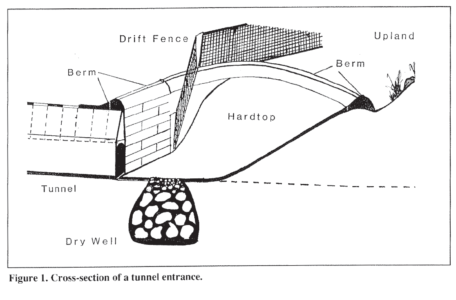

Three steps were taken to minimize flooding of the tunnels (Figure 1)

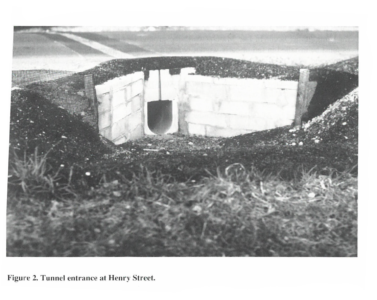

- An asphalt pad was designed for each of the four tunnel entrances, which, as well as stabilizing the slope, provided a 15 cm berm to shunt water away from the tunnels (Figure 2)

- At the base of each pad drywell (soak-away) was installed extending 0.5 – 1 m below the surface to collect any water reaching the tunnel entrance.

- Drift fences were constructed from plastic mesh to allow water to flow through, rather than along, the fences. 6 mm mesh was used on the upland side of the road, 3 mm mesh (to stop the young of the year salamanders)m was used on the pond side.

Result: Flooding was not an issue.

Drift Fences

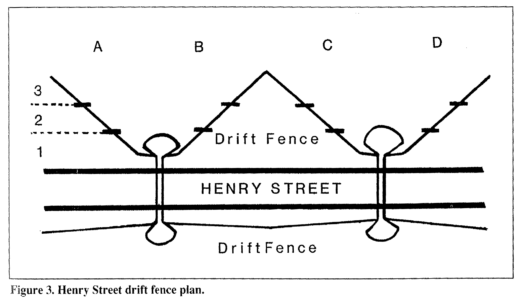

Drift fences were built on the upland side of the road to angle out from each tunnel. Straight fence was used on the pond side due to landowner considerations.

The upland fence consisted of four wings (Figure 3), A and B, which led to the north tunnel, and C and D leading to the south tunnel. Each wing was divided into three sections, each about 10 m long. Migrating salamanders were counted and the wing and section where they first encountered the fence was recorded.

Salamanders were marked with either paper dots or identified by charting their distinctive spot patterns. Dots with small amounts of glue were applied with forceps so as not to detain or disrupt migrating salamanders. Fence efficiency was calculated as the percentage of animals encountering the fence that actually passed through the tunnels.

Result: In the first spring 68.4% of the marked salamanders successfully passed through the tunnels. Fence efficiency for wings varied from 64% to 76.9% Fence efficiency was lowest for animals that encountered the fence closest to the tunnels.

Effectiveness of Tunnels

Salamanders were observed at the tunnel entrance to see how they reacted to the tunnel. The number of animals reaching the tunnel was counted and the number of those that passed through, as opposed to turning away, was also counted. ‘Tunnel efficiency’ was calculated as the percentage of salamanders reaching the tunnels that actually passed through.

Results: 75.9% of the eighty-seven salamanders observed at the tunnel entrance passed through. Salamanders that did not go through generally hesitated before the entrance and then turned back. Even among those animals that passed through, some turned away, returning several times before going through. Several explanations exist for the ‘tunnel hesitation’ including differences in temperature, humidity or light, air flow, or human disturbance.

*Langton, T. E. S. (1989). Jackson, Scott and Tyning Tom: Effectiveness of drift fences and tunnels for moving spotted salamanders Ambystoma maculatum under roads. In Amphibians and roads: Toad tunnel conference: Papers and discussions. ACO Polymer Products.

Amherst Tunnel, 25 years after installation